I am at the barber’s, and a copy of Paris-Match is offered to me. On the cover, a young Negro in a French uniform is saluting, with his eyes uplifted, probably fixed on a fold of the tricolour. All this is the meaning of the picture. But whether naively or not, I see very well what it signifies to me: that France is a great Empire, that all her sons, without any colour discrimination, faithfully serve under the flag, and that there is no better answer to the detractors of an alleged colonialism than the zeal shown by this Negro in serving his so-called oppressors

- Roland Barthes, 1957

Thus opened Barthes’ commentary on how signs are worked into myths in the contemporary world. Of course, if Paris-Match had wanted to use a real example of a “Negro in a French uniform,” the obvious choice would have been Touissant L’Ourvertoure, that most loyal servant of the French Republic and leader of French Haiti during the most tumultuous years of the Revolution. But we all know how that loyalty was repaid by the French – Toussaint was tricked, kidnapped and left to starve to death in a Parisian dungeon. Better to invent an example.

Rishi Sunak is no Touissant. L’Ouvertoure made it his life’s mission to overthrow slavery and never allow it’s restoration; Sunak’s is to ensure that the global system of neocolonial wealth extraction – encompassing a greater degree of enslavement than at the height of the Maafa – continues unabated. This requires an undying attentiveness and loyalty, above all, to counter-revolution.

Core to that strategy, since the days of Disraeli, has been to allow a growing proportion of the domestic working class a share of the fruits of imperialism, thus creating in them a direct interest in the maintenance of the system. Hand in hand with these material benefits has been the psychological kick of being constantly flattered about being part of a master race or superior civilisation. This was what WEB DuBois termed the “wages of whiteness,” although in Britain it was always membership of the British empire and its civilising mission that was primary more than mere whiteness alone. Boris Johnson’s particular style of ‘populism’ understood these twin pillars of counter-revolution – the material and the psychological – very well. On the material level, he favoured a certain leftish economic rhetoric, embodied by the commitment to ‘levelling up’ (to be achieved by a promised, albeit never materialised, massive state infrastructure investment in the deindustrialised North) and signalling an end to a decade of austerity. This involved removing (briefly) the public sector pay freeze, making more nurses and more hospitals a major plank of his election campaign, and using £70 billion of public funds to pay wages during lockdown.

Running alongside this ‘big state’ economic platform, however, was a crude nationalism punctuated with explicit dogwhistles to the far right. Johnson’s three-pronged approach combined braindead feelgood claims of British greatness with the frequent mocking of persecuted minority groups, all conducted against a backdrop of ceaseless media-grabbing attacks on migrants and foreign entities in general (the EU chief amongst them). In other words: mock the minorities, fuck the migrants, up the Brits. This was, or at least claimed to be, a welfare state of sorts, but only for the in-group, the volk (as defined by birthright or perhaps, where unavoidable, economic necessity). Let’s not get hysterical and call it fascism. But it was clearly in the fascist tradition.

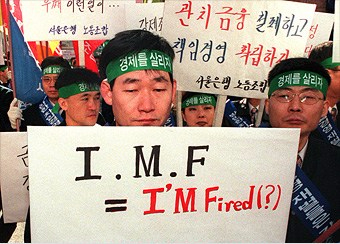

To fend off such claims, Johnson recruited a steady stream of Black and Brown faces to front the persecution. Priti Patel would head up the war on migrants, Sajid Javid the hostile environment in the NHS, Kemi Badenoch the culture war against those who would dare criticise the empire, and Suella Braverman the rooting out of judicial opposition. Ever since NATO recruited Barack Obama to launch its war on Africa in 2011, Blackfacing racism has become the standard practice of imperialism. But it has a long pedigree: a century and a half before this, Sunak’s moral forbears were making themselves available as the native face of British oppression in India.

But where does Sunak himself fit into this? He was Chancellor, much more obviously involved in the ‘left plank’ of the populist agenda than the right; come the Conservative leadership contest, he had a lot of ground to make up. Already racially suspect for the white-and-proud Conservative membership, he had to prove himself twice over – one, that his loyalties were to his nation of residence and citizenship, not his familial homeland, and two, that he was willing to bash the (racially) undeserving poor as well as splash the cash. He did his best on the campaign trail: railing against ‘woke nonsense’ and the Equality Act, threatening to criminalise criticism of Britain, and promising to prioritise a crack down on the desperate families drowning in the English Channel should he be elected. But it didn’t work; the white conspiracist gerontocracy that is the UK Tory party rejected him in favour of the more reliably unhinged Liz Truss by a comfortable margin. But now, barely two months later, she is out and he is in – and the ‘left plank’ of Johnsonian populism is being readied for the bonfire. The markets – that is, the billionaire investor class that Sunak is very nearly a member of himself – have dictated that it is time to balance the books, and new Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has promised a new round of crippling austerity as a blood sacrifice. The material wages of whiteness – and of imperial citizenship – are set to become very threadbare indeed.

The problem is, it is pretty much universally acknowledged that it was precisely this populist combination – of leftish economics and rightwing culture wars – which delivered the so-called ‘red wall’ – and thus the election – to the Tories in 2019. These former Labour seats, even more than the rest of England, are nationalist and anti-migration but also supportive of public services. With no good news on the latter, Sunak’s government will be increasingly seeking to double down on the nationalist side of the offer to maintain their electorability.

This explains the prominent positions given to leading culture warriors in Sunak’s cabinet. Sunak was willing to take the flak for awarding the Home Office portfolio to Suella Braverman less than a week after she had been forced to resign from the same position for repeatedly breaking the ministerial code – because he knew he needed someone like her to shore up his migrant-bashing credentials. Days later, it emerged that she had broken the law to overrule official advice on migrant accommodation, creating a dangerous level of overcrowding in the Manston refugee holding centre. These types of scandals are not, however, as the bourgeois liberal press believe, electorally damaging. Quite the opposite – they replicate the winning Johnson formula of demonstrating contempt for namby pamby laws that get in the way of delivering on the promise to properly persecute migrants. Johnson’s mistake was merely to believe that the public sympathy he won for breaking laws meant to protect migrants would be extended to cover breaking laws meant to protect white grannies. He learnt the hard way that his mandate, like so much in Britain, was a racialised contract, not a blanket one.

Likewise, the lies. In the Trump-Johnson era, ‘telling the truth’ no longer means making factually accurate statements, but rather saying things that are gratuitously offensive to vulnerable minorities, regardless of their veracity. In this sense, Braverman is ‘telling the truth’ when she says Britain is facing an “invasion” by “unprecedented” numbers of asylum-seekers arriving in the country. Whilst factually inaccurate, of course – clearly there is no military offensive underway by the desperate and half-drowned washing up on Dover’s beaches, and actual numbers of asylum applications are 40% lower than they were in 2002 – Braverman is nevertheless perpetuating a popular scapegoating of those arriving, and that is what counts. One might wonder whether it would take a violent fascist attack to make the Bravermans of the world question their role in legitimising the demonising tropes of the far right. But such an attack had already occurred just the day before she made her comments, when a fascist threw three petrol bombs into a migrant processing centre in Kent. Whilst even her own immigration minister distanced himself from her comments, Sunak stood proudly by her. With the wave of crushing attacks on working class living standards now brewing, it is only the psychological wages of whiteness – the pride that comes from spitting on the wretched of the earth – that he can now fall back on.

Nothing illustrates this more clearly than the Conservatives’ grim determination to ensure the spectacle of desperate channel crossings continues. They could, of course, end the situation overnight, by the simple act of setting up an asylum processing centre in France, removing at a stroke the sole purpose of the dangerous crossings. This is what refugee charities have long been pushing for, and was indeed offered by Macron this time last year, only to be rejected out of hand by Johnson. Instead the government is committed to ensuring that the only possible way to apply for asylum in the UK is to risk life and limb on the high seas or in the back of a lorry.

Keeping immigration alive as an issue is a fundamental electoral strategy for the Conservatives, as immigration is one of the few policy areas in which they are traditionally more trusted than Labour. And it is not necessarily easy to do so, given that the UK is only 18th in Europe in terms of asylum applications per capita. Maintaining a constant spectacle of death and crisis on the South coast is one way in which immigration can be kept at the top of the agenda, giving the Conservatives an opportunity to simultaneously demonstrate their ‘toughness’ and keep attention away from things such as crumbling wages, unaffordable housing and the collapsing NHS.

In this, they can rely on the collaboration of the mainstream media, who dutifully neglect to mention that the crisis is a deliberately manufactured spectacle caused solely by the refusal to process asylum claims in Calais. In a detailed and sober piece on the BBC news website, for example, entitled, “Why do migrants leave France and try to cross the English channel?,” it is not even mentioned. Clearly, the ruling class commitment to keeping the refugee in the role of the nation’s whipping boy seems set to continue. Whether this can compensate for the ever sharper deterioration in national living conditions forever remains to be seen.

This article was originally published in Counterpunch in November 2022.